Henrico’s mental health response expands, evolves with empathy, coordination

The 911 call came in just after noon: A woman reported that her 27-year-old friend had a serious drinking problem and might be suicidal.

A dispatcher marked the call as Level 4 – the most serious – under the Marcus Alert system, which is designed to help responders manage behavioral health emergencies so individuals in crisis can get the treatment and resources they need.

Henrico Police Officer Logan Miller, already in the community with the county’s Mobile Response Team, heard the request for service. He confirmed his unit was nearby and would respond immediately.

As Miller drove – without turning on his vehicle’s emergency lights and siren – mobile response clinician Sophia Hartman checked a database on her laptop and found the 27-year-old man had received services through Henrico Area Mental Health & Developmental Services (MHDS). She had counseled him a few weeks earlier, and he’d missed a follow-up appointment.

Within minutes of the 911 call, the Mobile Response Team of Hartman, Miller and Police Officer Greg Anchor had arrived at the family’s home to find the man visibly distraught and standing in the driveway with his father. As the three approached, Hartman gently introduced herself.

“It sounds like things have been really tough,” she said.

“An understatement,” he responded.

*****

The Mobile Response Team and Marcus Alert system are the latest additions to a public-safety response system that’s evolving to address not only immediate threats to life and property but also the specific challenges and needs of individuals who are struggling with mental health and/or substance use.

Henrico’s efforts are rooted in empathy, compassion and coordination among agencies. They emphasize building and strengthening relationships and steering individuals toward treatment, community resources and support. The goals are safety and prevention, avoiding hospitalizations and incarcerations whenever possible and reasonable.

The focus on behavioral health began formally in 2008, with the creation of the Crisis Intervention Team, which includes representatives of the Police and Fire divisions, Sheriff’s Office and MHDS. Since then, Henrico added the Services to Aid Recovery (STAR) team in 2012 and the Mobile Response Team (MRT) in 2023.

The county now has two MRT units, which travel throughout the county to provide immediate and follow-up care for individuals in crisis. The units operate weekdays from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. and include specially trained police officers and a mental health clinician.

“We go out in the community and try to help people who are having tough times,” said Anchor, a longtime officer who has spent the past 3½ years in the Prevention Services Unit, which oversees the MRT and other specialized units. “We see people who are having their worst day. We’re trying to prevent bad things from happening by getting to them early.”

In some cases, an individual might be receptive to getting help but doesn’t know where to start, Hartman said.

“My favorite line to everybody is, ‘You don’t have to do it by yourself. Let’s walk through this,’” she said.

Sometimes, she added, it’s as simple as offering food to someone who’s hungry or consoling them as they cry.

“I’m here to meet you where you’re at, and that’s really hard to do when you’re in the office,” said Hartman, who joined the MRT in August 2023 after earning a master’s in rehabilitation and mental health counseling from Virginia Commonwealth University.

Miller said he appreciates the opportunity to help someone who’s struggling but acknowledged that some, in a moment of crisis, don’t see it that way.

“I do feel like we’re able to get people some help,” he said. “Sometimes, you break the cycle of what they’re going through.”

*****

One day in late November, the MRT partnered with Fire’s CARE (Community, Assistance, Resources and Education) team and spent the morning driving throughout eastern Henrico, checking on residents with various mental health and substance-use issues.

Their list included a woman who had called 911 several times over a period of days for treatment associated with addiction and a young man who had stopped taking his prescriptions for schizophrenia and had ended up at a fire station seeking mental health treatment.

At the first stop, no one answered the door, so Hartman left a flyer on MHDS’ same-day access treatment services. She managed to reach the woman by phone and learned she was hospitalized.

“I just wanted to touch base to see how you are doing and see if there’s anything we can do for you,” said Hartman, who assured the woman she’d stay in touch.

Next, the group checked on the man who had stopped taking his medication for schizophrenia. They ended up chatting with him and his father outside their home. They emphasized the importance of staying on prescribed medications and of calling 911, not driving to a fire station, if there’s a medical emergency.

“I thank God for y’all coming down here,” the father said before the group headed to their next stop.

*****

In 2020, the Virginia General Assembly adopted legislation requiring localities to establish a Marcus Alert system, with protocols aimed at ensuring behavioral health responses to behavioral health crises. The law was named for Marcus-David Peters, a teacher who was in the middle of a mental health crisis when he was fatally shot by Richmond police during a confrontation in 2018.

Henrico’s system, launched in July, includes several main components. A database allows community members to voluntarily share contact and mental health information that could be helpful to emergency responders. The database, which isn’t accessible to the public for review, has 26 entries.

Now, when a 911 call includes a name, address or other information that matches the database, Henrico’s computer-aided dispatch system generates a message noting the possible connection and a need to cater the response – for example, by dispatching the MRT.

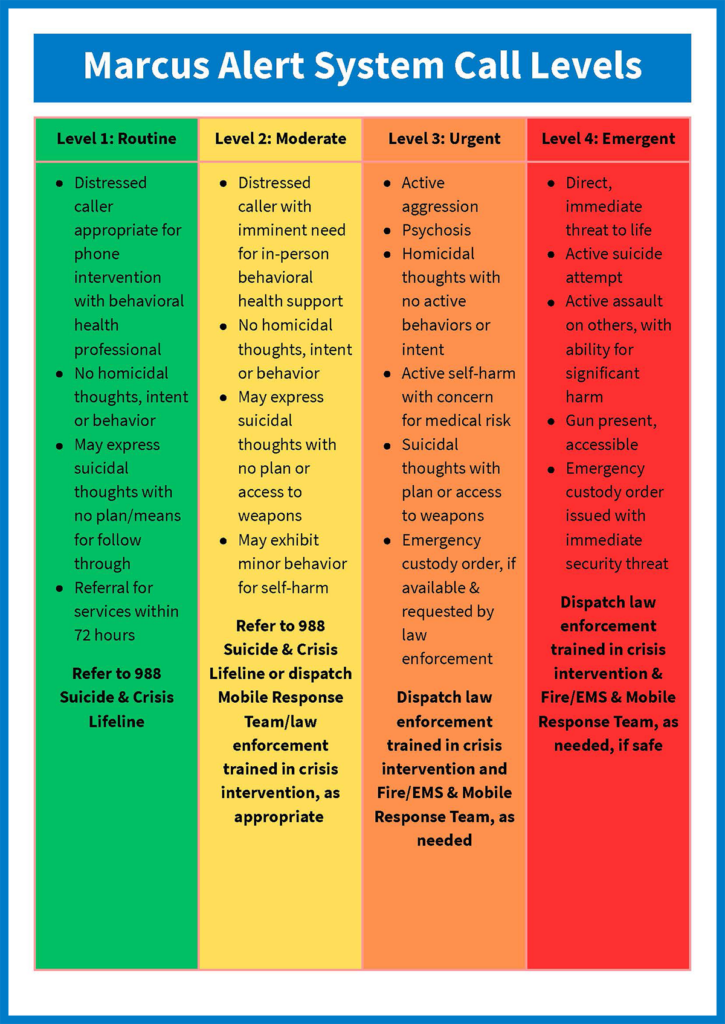

In addition, when a 911 call includes a possible mental health concern, such as a person with suicidal or homicidal thoughts, a dispatcher will assign it to one of four levels of urgency for follow up.

For example, calls marked Level 1, or “routine,” could involve someone in distress but with no plan for self-harm. Those calls are forwarded to the 988 regional crisis call center.

Higher-tier calls, including Level 2, “moderate;” Level 3, “urgent;” or Level 4 “emergent,” generate more resource-heavy responses, such as dispatching the MRT, mental health clinicians, police officers with training in crisis intervention and/or emergency medical personnel.

Through its 911 system, Henrico logged 415 Marcus Alert calls from July through September, according to the Department of Emergency Communications. The breakdown by tier was: 104, Level 1; 91, Level 2; 119, Level 3; and 101, Level 4.

The system has rolled out smoothly and hasn’t significantly altered the response to health calls, officials said. “We were already kind of doing it,” Miller said.

“I feel like we’re more aware of what’s going on in different parts of the county,” particularly rural areas, Hartman said.

*****

In the MRT’s third stop of the day, Miller attempted to speak with a man who had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and was reportedly no longer taking his medications.

After failing to persuade the man to open his door and engage, Miller and the rest of the team decided they’d done all they could for the day. They left a flyer for MHDS services and headed to their vehicles.

“We’ll keep him on the list,” Hartman said.

For information on same-day access to services of Henrico Area Mental Health & Developmental Services, call (804) 727-8515.

If you or someone you know is in crisis and needs immediate help, call emergency services (804) 727-8484, the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline or 911.